All I have to show today for my fifteen year career in amateur auto repair is my toolbox. I never sold it, although it has done little except take up space since the middle nineties, when I donated my old bus to a local church. The box gathered dust quietly in my apartment closet through my Los Angeles teaching and TransitPeople years. It might have aroused suspicion among the fellow transit geeks who visited me there, had they known about it, like a jar of meat tenderizer on a vegan’s spice rack.

Today I am grateful I still have it; I can flick open the latches and look inside, like an historian cooing over artifacts in a time capsule. Look! Loctite! What mechanic wouldn’t have Loctite? I had use for it, too, I see; there’s a crumpled tube, between a spool of 18 gauge wire and needle nose vise grips. My feeler gauges are still in the box, tucked under a 3/8″ drive socket set. The non-mechanics among you reasonably expect that a leering term like “feeler gauges” must preface a smutty joke. I’m sorry; I have none to offer; feeler gauges are indispensable for setting the valve lash on ridiculous old Volkswagens like my bus. I used them often.

I was an amateur. If you tell a pro that your author could assemble and install an engine from the long block up, but never bolted in connecting rods or rod bearings, she will accurately gauge my expertise, or lack of it. I now think I was psychologically ill-suited for the hobby, like a wallflower who bulls his way through Toastmasters sessions. I entertained occasional, vague thoughts of making a career of it, and am sure I would have suffered if I had.

But I sampled the life. Computer-controlled modern cars may be too difficult for most amateurs to tinker with; the hobby may have drifted thankfully toward oblivion, like wind-up watch repair or the craft of maintaining outhouses. But hundreds of thousands of Americans grew up wrenching and twisting and cursing bitterly at things under the hoods of cars, and will identify with the reminiscences that follow. No matter what else they might think of me.

* * *

In the early nineties I read a magazine profile of a multi-millionaire who was also a gentleman mechanic. He had outfitted the garage of his posh estate with a full set of professional tools — everything he wished for from the Snap-on catalog, undoubtedly — and the breadth of his manicured lawn set the garage far enough back from the street so that no unaristocratic drilling or hammering sounds would reach a neighbor’s ear. He worked only on elderly European sports cars that were as blue-blooded as the neighborhood, and may even have had a floor lift put in to elevate the Jaguar or Porsche from the spotless garage floor, so he would not have to contend with exasperating scissors jacks, or, worse, actually crawl on the floor and dirty his shop clothes.

The article included photos. There were big tool chests against the walls, and the chests undoubtedly included neat little clean-scrubbed plastic bins for every conceivable size of nut, bolt, washer and machine screw that might one day be necessary to repair a fancy sports car, as well as the wrenches and sockets to fit the bolts, and 1/4″, 3/8″ and 1/2″ socket extensions.

The wording of the paragraph just past may suggest that I regarded the gentleman mechanic with some resentment. (Boy, did I.)

I’ll bet this gentleman really enjoyed his time in that garage. One can imagine oneself in his shoes: calling The Boy to get the Jag up on the hoist, donning a fresh pair of coveralls, plucking the proper socket out of the chest and hearing the gratifying snick of the socket popping into place on the jewel-like Snap-on ratchet. Waiting just a bit irritably while The Boy arranges the shop lights, and then doing something to the undercarriage. Perhaps tightening shock absorber nuts (why not?), or fitting a new cotter pin into the steering assembly, or attempting a more ambitious job. If it didn’t go as planned, as automotive jobs sometimes don’t, one could leave the car on the jack with a shrug, and set off for the office in the limo.

Amateur auto repair is not usually like this.

Sometimes, true, it’s not that bad. The amateur may be more like the multi-millionaire than like me; he may labor in a decently-equipped home garage, with a handsomely furnished tool box. Or, more significantly, the job may be planned. It’s time for the oil change. The weather is agreeable; there’s plenty of time; you’ve got the oil, the filter, the oil pan, all the tools you need, and the tools have been retrieved from the nooks and crannies they might have squirreled themselves off into, and cleaned, and made ready. Sure, the oil will splash on your fingers when the oil drain bolt comes out, but so what? The sun is out. You’ve got space and time. You might enjoy yourself.

Too often, amateur auto repair is not like this, either.

Amateur auto repair is often undertaken out of necessity by folk as poorly heeled as I was in my twenties. As they can’t afford professional mechanics, they also can’t afford anything by Snap-on (which doesn’t send reps to show catalogs to destitute rubes with no money), or bountifully-equipped tool and socket sets, or every arcane tool their steeds might unexpectedly require for the completion of some obscure task. They may not have neat garages at their disposal, to protect them from the elements. They may work illegally at curb side, surrounded by traffic and justly glowering neighbors, and vagaries of weather.

Worst of all, the cars they work on are not Porsche cabriolets or E-type Jaguars or Ferraris. They may drive junkers and heaps and buckets, and the junkers and heaps and buckets feel shame for what they are (or at least as much shame as a car can feel), and yearn neurotically for death, eternal sleep, a final reunion with the other unwanted cars in the wrecking yard. They may seek to hasten their deaths by breaking down just when their owners most need them and are least prepared to attempt repair.

Amateurs often work on cars in the driving rain, wind and snow, with ineffectively jerry-rigged tarps flapping over their heads and frozen fingers grasping for nuts and screws. They drop the nuts and screws, and the nuts and screws don’t roll onto the shop floor. There isn’t a shop floor; the nuts and screws roll into the gutter. Amateurs discover mid-way through repairs that, gee whiz, they just can’t find the 13mm socket they’ll need to get the dohitzit off, even though the socket was in the tool box yesterday. Now it’s somewhere else, and their curses don’t make it appear, and they spend an hour trying to hunt it up.

Or, better yet, they realize halfway through the job — with the car absolutely inoperable, with tools and parts everywhere and their persons liberally coated with grime — that they don’t have the extension or the special socket or the weird wrench necessary to get the dohitzit out or bolt it in place. There is nothing to do but push everything into a discreet pile under the hood or chassis, and drive to the parts store to buy or rent one.

But whoops, you don’t have anything to drive there in. Do you? You’ve administered knock out gas to your car, sapped it unconscious. You curse and swear, but no one listens. You call a friend. You ride the bus. You walk.

This is amateur auto repair.

Amateur mechanics also vary widely in knowledge and experience. Many have only a fuzzy idea of how to complete the repairs they undertake, like fifteenth century explorers launching caravels across the Atlantic. The ability of a Laurie Gerrish or a Jim Dilamarter or of any the elite race mechanics interviewed for Brothers of the Milky Way is a remote, unobtainable, almost unimaginable thing, like daybreak in Andromeda.

Amateurs seek out other amateurs for advice. If they are lucky or careful or both, they may stumble into someone who knows more than where the front bumper is. This acquaintance becomes a sage, a guru, and may protect the acolyte from calamity. But amateurs often fail to find gurus. Instead they buddy up with other ill-informed amateurs, and share bad advice. If you don’t have a torque wrench, why, just pull until it feels snug! What I always do is put some extra in over the fill line. Just for a margin. Amateurs fawn over speed equipment catalogs, believe the shameless lies they are told in them, and flush discretionary dollars on parts that work half as well as original equipment, but cost twice as much.

* * *

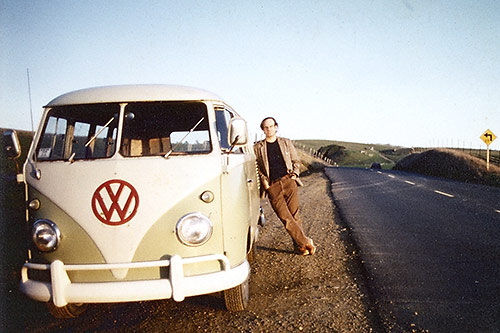

Most of my mechanicking was done on the preposterous old bus described in Why I wrote Brothers of the Milky Way. (I include another photo, above, just to give you something else to look at. Expect a fat bill by email.) After about a decade, I had concluded that the hobby had been a mistake, that the trials I endured as an amateur were a kind of Dostoyevskian punishment inflicted by self upon self for ever fancying myself an artist. But by then I had transformed the bus’ interior into a rolling office, with louvered windows, stove burners, icebox, chemical toilet, heater, bed, 12 volt fan, and, best of all, a manual typewriter and typing table bolted firmly onto the floor pan. I could go off on writing expeditions into the country in my camperized bus, and was fond of these, loathe to give them up. Further, I knew how to work on the darn bus by then. And I already had my tools.

I will credit a casual remark by one of my mechanicking gurus for plunging the fatal stake into the heart of my hobby. Bob no longer repaired cars professionally, but had labored as a full-time Volkswagen dealership mechanic for eight years before we met. He owned a ’67 split-window, little different mechanically from my ’59. He also owned a newish Toyota.

One evening, we discussed a road trip that Bob planned for some out-of-California attraction. Reno, perhaps. Perhaps Las Vegas. I’ve forgotten.

“I was thinking of driving the bus,” Bob said, “but then I thought, ‘Well, what parts will I have to bring this time?’ I’m just going to take the Toyota.”

Bob never knew how solemnly I reflected on this remark in the months that followed.

For eight solid years, he had worked as a professional, full-time mechanic at a Volkswagen dealership. After those eight solid years, he was still captive to the fact that a car incorporates tens of thousands of moving parts determined to fall into disrepair as the car grows older. If you want reliable transportation, you simply have to budget for something relatively new … or better still, move to a city with a good transit system, so you don’t have to drive often, or ever.