San Francisco’s brightest and most vital blocks may be on Mission Street. I include nearly every blood-throbbing centimeter between 25th and 22nd, then some of the homely and magnificent acres north and south.

These blocks are only occasionally and accidentally pretty, and not a safe bet for some tourists. Attractive or not: San Francisco is at its most alive on them. The felon freshly disgorged to freedom after decades behind bars, with gate money and ill-fitting clothes; the last-will-and-testament writing terminal cancer patient, told that it’s not melanoma after all; the grim, waters-of-the-Golden-Gate-contemplating would-be suicide, who decides to give the world one more try: to these blocks of Mission Street they can come to drink in raw, skin-blistering life through their pores, to count themselves among the living.

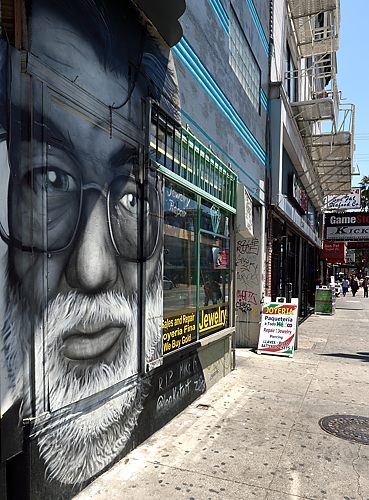

Walk in the sun on the east side, by Imperial Travel, Lucky Pork Market, Sun Fat Seafood, among odors of sweat, exhaust, empanadas, marijuana; sidestep workers, loungers, drifters, giggling kindergartners leaping sidewalk cracks, a leathery-cheeked Guatemalteco with crisp-molded tejano over brilliantined black widow’s peak, hawking sugary raspados from an ice cream cart. Feel your eardrums pulse with the mad dissonant ostinato of horns, whistles, catcalls, burbling exhausts, conversation snatches (I got HER name tatted here, ‘n’ she tatted MY name; I heard those very words on Mission, just last week), smooth-droning trolleys, the newsrack-rattling subterranean roar of a passing BART metro. Many, many San Francisco blocks are wealthier, prettier, safer, cleaner; only Market serves up life as intensely.

Who made it so?

I walked Mission shortly after my return to the Bay Area in 2011, still remember the uncomfortable wonder I felt, the disturbing sense that the whole of what surrounded me was larger than the sum of its parts. Too much larger; who had conspired, say, to paste up this protest poster (with grim, apocalyptic, fist-upthrusting Siqueiros marchers, in last stand yellow and black) next to the meek window display of a beauty supply house, plumping dainty chrome shears and curling irons on crushed red velvet?

Too many elements worked too well together; too many details had been primped, fussed over, tucked in. Any level-eyed rationalist would have attributed the pleasing aesthetics to happy accident, but I was skeptical. The furniture pieces of a perfect set don’t fly on a stage by themselves. I sensed a larger hand at work, a scenographer, a silent mastermind.

Perhaps Mission Street had a god.

Yes! That explained it! This was the fantasy that emerged during my Mission walks in 2011. Mission had a puppeteer, a demigod, foreman to some city acres, uninvolved with others, likely senior to deities that oversaw less demanding turf. (How much imagination would a god really need to run mostly-all-the-same Billionaire’s Row or Sunnydale?)

I contemplated a deified, beneficent Carlos Santana type — a natural, given the Mission’s Latino heritage — but was surprised that my imaginings wouldn’t be steered that way. Too predictable; the afterlife wouldn’t go in for such typecasting; no, the god of the Mission would be other-than-expected, a celestial Oscar Diggs, like a tweedy and apologetic Bennington MFA who offers a too gentle handshake to horrified fans of his ghostwritten Grunts on Guadal series at a book signing.

The character and Identi-Kit facial composite of this deity then matured so quickly and effortlessly in my mind’s eye that I took my imaginings half-seriously, admit to taking them half-seriously now. After all, we don’t really know about these things, do we? Didn’t Einstein meditate upon the weakness of human understanding of nature?

Maybe I just think this God-of-the-Mission bit is imaginary.

Maybe he’s a real He.

* * * * *

The God of Mission Street was a tall, slender, gay caucasian male in his last terrestrial incarnation, neither native son nor recent gentrifier. He aspired seriously to a design career before falling to AIDS in the worst U.S. years of the epidemic. Something Larger (about which I dare not speculate) took simple pity on him in the afterlife, requisitioned a minor divinity’s toolkit, promoted him to a Him. He wore his hair short in his mortal years, cut a preppy-flavored variant of the then-ubiquitous Castro Clone. The online B.A.R. obituaries include his mortal photo and bio, but He won’t reveal details of His past identity or year of death, despite our other confidences. Click through the obits, if you wish; your guess is as good as mine.

His taste is excellent. I picture Him in the other-worldly ether with a thoughtful fingertip poised on cheek, brooding over His dominion as an architect might study an N scale model, contemplating enhancement or replication of one scene element, elimination of another. The surly, beer bottle-brandishing drunk in the tank top — an obvious gym rat, dressed to flaunt weight room biceps and delts, eyes watery, lips stuporous under Fu Manchu moustache — would go well near the Mega Trading Company marquee, wouldn’t he? Let’s shoo him over there, encourage him to slouch on a parking meter. How about those polyester-suited Filipino oldsters handing out Bible tracts: too predictable in front of Bonita Footwear, aren’t they? Let’s move them in front of Anna’s Linens (or would that be too jarring? Hmmm.)

I’m afraid He isn’t a particularly nice god. How could He be? Life on Mission is often cruel. I wouldn’t waste breath entreating Him if struck down by a car; He’d only urge me to a curb where my blood and screams might juxtapose well with the newspaper racks. Vibe and aesthetics are His thing; thank Him for Mission’s character, nothing else. He shows no special allegiance to gay culture, and is not all-powerful; if He were, Mission Street would include only a few, specific chain stores. He occasionally asks me for feedback, as I am one of the few mortals aware of His existence, but only about aesthetics.

His era may be ending. I have kept quiet about the luscious vitality of these Mission blocks since 2011, for fear that even my scribbles in this modest blog might attract unproductive attention, but see no point in embargoing the news any longer. The Mission is changing, won’t be what it was. San Francisco is such a tech hub now; industry workers have moved into the district, transformed Valencia Street, are spilling onto Mission, too. The God of the Mission can work an occasional stray Python programmer into His aesthetic mix (plump, blinking, twenty-five, with unsuccessful hipster beard curling over a SourceForge t-shirt, frowning at his Tinder profile on his smartphone next to La Taqueria), but so many of the pearly-toothed Mountain View shuttle bus rider types are wandering onto Mission now. They change the mix of the cultural topsoil, as talented, hard-working and admirable as they might be; they encourage a different and less variegated flora than the Mission of old. The God of the Mission tries to coax them back to Bi-Rite and Dandelion and the Dolores Park hill near the J-Line, where they fit in splendidly, but that’s not in His territory and they won’t all go, and He can’t integrate all that remain. His time is ending. He doesn’t have the same material to work with, will have to move on.

But not today, not in the summer of 2015. Visit soon! Mission Street still feels mostly as it did when I marveled at it in 2011. Pretend that you just got out, or learned that it’s not malignant, or have chosen to risk one more day of life. Walk the brilliant, teeming blocks I’ve named, and try to glimpse the mastermind that made them so exquisite: contemplating His turf from a misty hereafter, brooding over His chess pieces.