5+ years in Spain, and I still marvel at Madrid’s subway like a first-time tourist. I sip tea out of a Madrid Metro coffee mug, festoon my refrigerator with Madrid Metro magnets, pay dues to Andén 1, a local enthusiast group, own their book about the metro and a thicker official history published by the transit agency.

(Although I still lack an official Metro doggie leash and Metro dog dish bowl. I know I’d certainly feel honored to eat out of such a bowl, even though I don’t have a dog. Should I splurge with my next pension check?)

My gushing may seem indecent to Europeans, who often take quality public transit for granted. It may seem worse than indecent to regular readers, who have seen this elderly transit fanboy blogger beat the subject to a bloody pulp in posts past.

Folks, I’m sorry. I spent most of my life in autocentric California. I still can’t believe how lucky I am.

A meeting at the Matadero for a riverfront hike, or a chat with a friend at a Cuatro Caminos café, or even a trip to the airport: I can just go, march, make with the feet, disappear into the nearest boca del metro with nary a concern for where and how safely I can berth an absolutely unneeded vehicle in the meantime. No repair, maintenance, or insurance tab, no hunts for cheap gas or safe parking, no stress if someone dinged a fender. It’s not just that I don’t need a car here, it’s that I can feel genuinely and wholly relieved to not have to deal with one.

I raved about Madrid’s Cercanías commuter rail in early 2017 and about the national high-speed rail network only a few months later. I continue to ride and fawn over both, but my true love is for the Madrid Metro. It is by metro that I do almost all my getting around in the capital. I see it as a major argument for a life in Madrid.

A SHORT HISTORY

Thousands of Madrid straphangers must pass daily beneath this ceiling-mounted Sol station sculpture, but I’ll bet that only a fraction notice or recognize the names shown. Echarte, Mendoza and Otamendi are the engineers who proposed a metro for Madrid in 1916. It would include four lines. The engineers wanted eight million pesetas to build the first.

‘A premature idea,’ thought many. Banco de Vizcaya ponied up half the pesetas, on the condition that the public contribute the rest. King Alfonso XIII helped save the day by pledging 1.45 million pesetas out of his own pocket. (Perhaps sacrificing funds that His Highness might otherwise have devoted to his royal porn collection.)

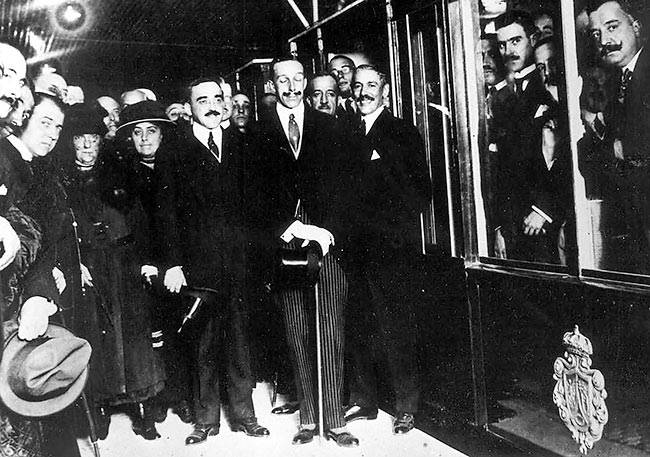

The metro would be and still is left-hand drive, as Spaniards drove on the left until 1924. The 1919 inauguration day photo was retouched to show the king with open eyes, and to splice in Echarte’s noggin over the king’s shoulder. Engineers Otamendi and Mendoza flank the king in both versions.

The metro remained open during the Civil War, transported coffins and cadavers as well as passengers. Citizens sought shelter and sleep on its platforms, as they would in London and Moscow during WWII. It recovered after the war, blossomed dramatically in the decades thereafter, and is today the third-longest rail network in Europe and the ninth longest on earth.

(Open rant: I don’t doubt that many Madrileños will attribute much of the growth to the clout of Spain’s construction lobby. Fine. Point granted. The great advantage of life in a country without a military empire is that a lobby that wants to coax moolah out of the public sector has to produce something that either benefits the public or at least looks like it could. In the U.S., the military-industrial complex can flush hundreds of billions yearly for the benefit of virtually no one, with only a voice-in-the-wilderness Quincy Institute to protest. Close rant.)

A transit infrastructure that shrugged off a civil war will shrug off Covid, too. I can offer no professional interpretation of transit stats, but the figures shown for the final months of 2021 (in the second xls file) look impressive to me. The metro feels nearly as busy today as it was pre-Covid.

TRANSIT AND COVID-19

‘[Covid-19] transmission isn’t happening in public transit,’ says Columbia University epidemiology prof Wafaa El-Sadr. A Scientific American article says about the same. In social settings, yes, with unmasked families and friends. In bars, gyms, indoor restaurants, at church. On transit, no.

I thought otherwise when the pandemic struck, and resigned myself to Covid infection when I stubbornly stuck to the metro. Two blood tests and two PCR tests say I never got it. I suppose I could still, despite my vaccine and a booster shot, but now would be likelier to blame an unmasked conversation indoors than a subway ride.

I wear lightweight blue ‘procedure’ masks to reassure others or comply with social norms, but don’t expect these leaky, loose-fitting masks to provide much protection against Covid. I have stuck by an earlier resolve to never set foot in a metro station without an FFP2 mask. Many are available here; I found a brand that consistently fits my face snugly.

‘Transmission isn’t happening in public transit’ doesn’t mean that it couldn’t happen there, if and when riders lower their guards, ditch the masks and start hacking up spit on each others’ cheeks. Al fin y al cabo, a straphanger travels in an enclosed space with lots of strangers and limited air flow. I may ride with a mask from here on in.

THE MADRID METRO IS …

(♦) Functional, clean, egalitarian. Madrid’s station network boasts a few aesthetic standouts, but they don’t stand out far, and are encountered infrequently. That said, the straphanger also shall encounter no dungeons, like the Grant Avenue disgrace I photographed in Brooklyn in 2011.

I don’t remember ever seeing a dirty or rundown metro station in Madrid, and volunteer efforts have taken me to some poorly-heeled parts of town. Some stations in low-income nabes are newer and slicker than stations in the city center.

Molded plastic metro seats are of the ‘no-trust, no-cushion’ variety, like Montreal and New York, unlike Tokyo and London. Seat arrangement and provision suggests that Madrid assumes you will stand. The 10 line car interior above is typical.

(♦) Reliable. A breakdown on one metro line made me fifteen minutes late for one pre-pandemic weekend meeting. That is the only time the metro hasn’t gotten me where I needed to go within an anticipated time frame. Transit unions have convened occasional strikes related to asbestos poisoning, but Spanish law guarantees minimum service levels during such strikes. I boarded trains that were more crowded than usual, still got to where I had to go on time.

(On the other hand, a Renfe Cercanías strike did persuade me to take a cab for an Aranjuez errand last October.)

(♦) Safe, with a qualification. In 2019, a mentally-ill rider kicked a stranger into the path of an arriving metro at the Argüelles station. (Miraculously, without significant injury.) I can think of no other incident here that compares to the subway shoves I have read about in New York City.

The qualification: pickpockets. Madrid would have happily foregone the distinction of being named Number Four worldwide in a 2009 TripAdvisor survey. I suggest riding with valuables in inaccessible pockets (or pockets inaccessible to anyone who doesn’t know you very, very well).

(♦) Potentially confusing to some visitors.

New Yorkers are used to navigating a powerhouse metro network that links many rail lines. Other Americans, less so.

Metro systems evolve. Madrid began with the 1 line in 1919, added the 2 in 1924, the 3 in 1936, other lines afterward. A kluge, like the evolved human brain. The developed labyrinths inevitably confuse new visitors. Good signage can help, but only so much.

Madrid may especially confuse some visitors by giving platforms double duty as corridors, walkways. The rider who enters this boca at Plaza de España will see signage assuring her that she can board a 10 metro here. And she can … after descending to the 3 platform, walking to the opposite end of said platform and continuing to the escalators to the 10. What she just crossed was a platform for riders of the 3, but a walkway for her.

Grafting in pedestrian connections between stations also can be a strain. Madrid’s metro map shows a link between the Noviciado and Plaza de España stations. The underground tunnel is there, alrighty … and I found it myself after regularly using both stations for two years. (Admittedly, I didn’t look that hard.)

IS THE U.S. THROWING IN THE TOWEL?

A study for U.S. PIRG said that American millenials drive less, and favor alternatives to the personal car. This study was conducted before Covid, true, and a progressive, Ralph Nader-founded org like U.S. PIRG must be more inclined to reach such a conclusion than, say, the Heartland Institute. But it jibed with my seat-of-the-pants impressions before going expat. The young I met were likelier to regard cars as needed-to-go-from-point-A-to-point-B appliances than as lust objects. (Or as near shrines, as the protagonist of my great American novel saw his ‘Cuda. See? I worked in a plug.) If you had to own a car, fine. If you could do without, lucky you.

Environmental concerns may have kindled my interest in transit in the 1990s, but the advantages I see today in Madrid are purely selfish. Car ownership is expensive; more than $10K yearly in the U.S. Drivers can’t disappear into the nearest boca del metro; they have to park, return to fetch the flivver from the parking slot later, hope that no one dinged, stole or broke into it in the meantime. Accidents. Road rage. Masochistic relations with mechanics, with body shops, with car dealers. Issues with other drivers. And today I don’t have to deal with any of it.

I haven’t returned to the States since I moved to Spain in 2016, but post-Covid transit-related stories in the American press have been dismal, depressing. The Los Angeles Times reports a spike in violent crime on city transit, drastic cuts in bus service. The New York tabloid press screams about innocent Gothamites shoved onto subway tracks. A Washington Post opinion piece wonders if city centers will ever recover.

From abroad, it looks like Uncle Sam is shredding his bus pass. Any recent pro-transit, pro-urban trends in the U.S. pushed hard against the grain of a century of pro-car development and land use decisions. The wealthy U.S. could compete with Europe, at least in some cities, but has consistently chosen not to. The gap between Yankee transit and European Union transit already was stark, scandalous, embarrassing.

Then Covid struck. Why not throw in the towel, believe that Covid drove a knife into the heart of public transit worldwide, that what’s left is pathetic, decaying, dangerous? And how many American pols and opinion setters have lived long-term in a big league European transit city? What reason did the U.S. ever give them to see public transit as a serious alternative to the personal car?

The AI engineer who told me in 2018 that he couldn’t find quality gigs in Madrid today paints a much rosier picture. Tech giants are recruiting here, he said; he regularly receives job offers. Young coding wunderkinds who can work from home have reasons aplenty to choose a city where they won’t miss a personal vehicle. And many will want to, despite Covid, if there’s any truth at all in that U.S. PIRG survey.

The U.S. seems determined to send them a clear message: move to Europe. I don’t see how this attitude benefits the United States.

CAVEATS AND QUALIFIERS

(♦) My personal post-Covid transit riding experience is limited to Madrid and what I saw in Switzerland last December. I would be shocked if cities like Stockholm and Copenhagen let their transit grids deteriorate post-Covid, but haven’t recently seen them with my own lying eyes.

(♦) Madrid’s transit grid doesn’t serve everyone. A language teacher stationed in Aranjuez — far from the Cercanías station there — described a miserable daily commute. A regular intercambio participant said his home-to-work shlep from the city outskirts would take twice as long by transit as it does by car. Drivable roads go to more places than transit routes.

(♦) I wouldn’t recognize all Spanish politicians, but have never seen one I do recognize on the metro.

(♦) The farther one lives from an urban center, the more necessary a car may be, and the more comfortably a personal car may fit into day-to-day life. They still break and have to be insured, true, but parking spaces are more plentiful, and driving stresses are fewer. I stand by observations made in a 2018 post.

For full-size versions of some of the shots above, please visit the photo directory.