Or my interpretation of the history, at least, as shall be presented tomorrow at a meeting of Andén 1, a transit enthusiast group in Madrid. President Eduardo Gallego suggested the talk. I combed through my collection of transit-related books, articles and bookmarks, wrote up the remarks that follow. If I post now, I’ll have a link that listeners can load on their móviles if the projection TV won’t show visuals. Color me cautious.

I’ll speak in Spanish, and no, I won’t read word-for-word. Andén 1 members may prefer to read the edited, footnoted text than endure my accent for 30+ minutes, but they’re fellow transit geeks, and thus must suffer.

I have omitted the second part of my presentation, a touristy overview of Los Angeles’ current transit grid.

Thank you all for coming, and thanks especially to Eduardo for inviting me. My presentation will be about public transit in Los Angeles. I lived there for many years — including a full decade without a car — and led TransitPeople, a nonprofit that conducted trips for children using the transit system. I also was a proud member of an enthusiast group similar to Andén 1: SO.CA.TA. (Southern California Transit Advocates).

This presentation will be in two parts. In the second, I’ll provide an overview of Los Angeles transit services available today. First, though, I must begin with the history. A hundred years ago, the Los Angeles region had the largest electric interurban railway system on the planet. Today, it is often seen as a public transit worst example. Why? What happened in the interim?

I didn’t fully understand it when I lived there, but see now that the die was cast through developments and decisions made long before I moved to L.A.. In most ways, the die was cast before I was even born.

My history is in five parts: of an empire, an invention, a turning point, a conspiracy, and finally, most recently, a missed opportunity.

EMPIRE

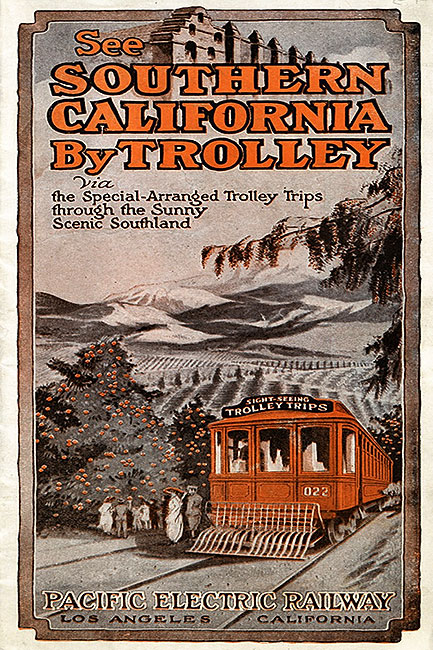

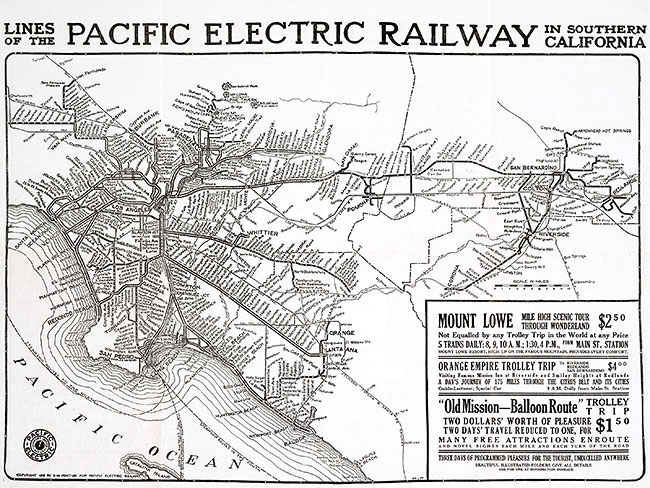

Behold, please, this map of the Pacific Electric railway network in Southern California, circa 1912.

I still can hardly believe that Southern California ever supported so huge a rail public transit infrastructure. A few comparisons, to give a sense of size: the fifty-three kilometer distance from Los Angeles to Santa Ana is only a few kilometers less than the distance from Puerta Sol to Guadalajara. The ninety-six kilometer distance from Los Angeles to San Bernardino is just a few kilometers more than the distance from Madrid to Segovia.

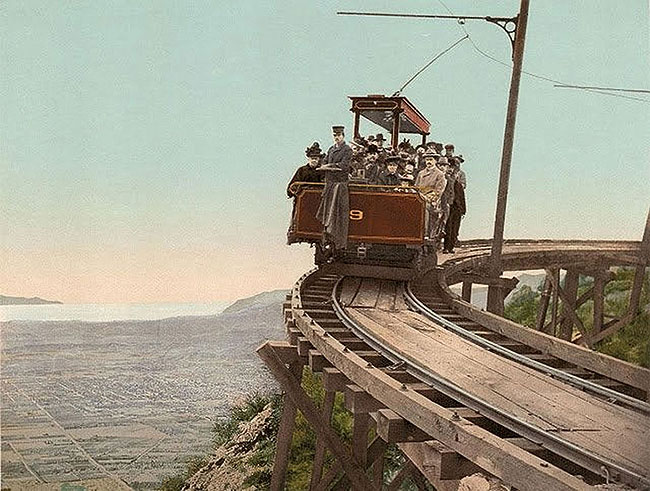

And this network existed a century ago! It wasn’t a fantasy. It was real. 1,600 kilometers all told, supporting over 2,000 daily trains. It even included a scenic line that went to a resort in the mountains. It was the world’s largest interurban electric railway system.

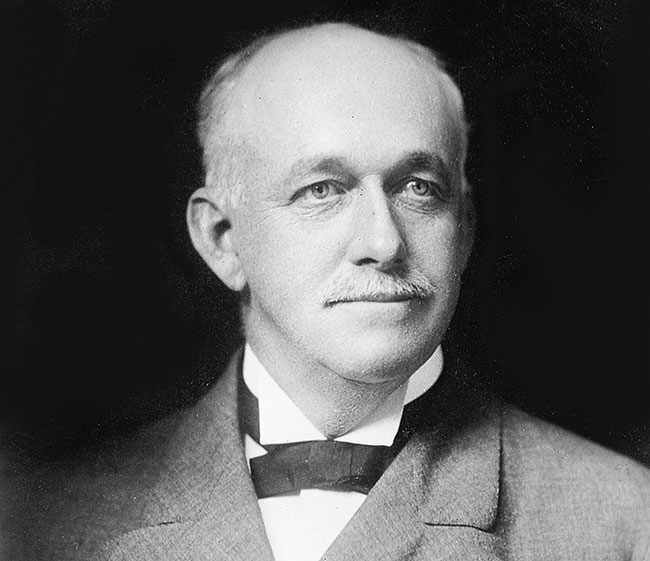

The network was the progeny of this man: Henry Huntington. It wasn’t a work of charity. Huntington made a fortune on land development: buying rural land on the cheap, connecting it to his expanding rail grid, re-selling the land for a profit. The system wasn’t ideal. Riders complained that the P.E. ran fewer cars than necessary to save money, forcing riders to stand. The grid also lacked radial connections. 1 But I believe that most any transit buff seeing this map without knowledge of the region it represents would predict that it would mature into a major transit metropolis.

Alas, this was not to be. And much of the reason can be attributed to the next part of this presentation, the invention. The personal car.

INVENTION

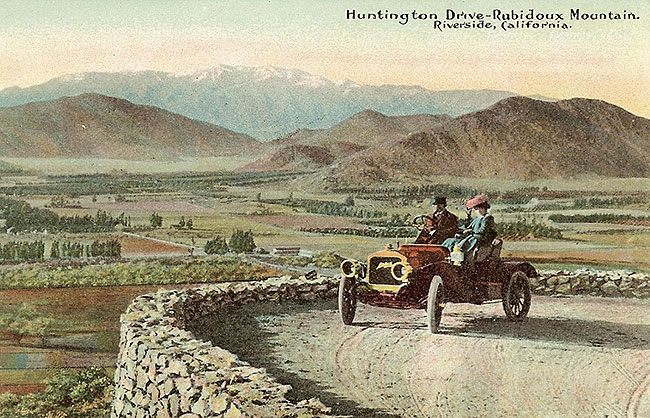

Early cars were open-top pleasure vehicles, intended more for recreational jaunts into the countryside than for purposeful travel from Point A to Point B 2. They caught on much faster in Southern California than elsewhere in the U.S., because Southern California sunshine allowed cars to be driven year round 3.

Early cars improved rapidly. Electric starters. Pneumatic tires. Henry Ford built the Model T, sold it in 1915 for a mere $390. (The equivalent of €11,260 today.) Cars already were popular in Southern California. How surprising was it that Angelenos began to use their cars for workday commutes?

At first, the Los Angeles press barely noticed the impact of auto commuters on downtown traffic. Then the problem mushroomed. By 1919, downtown Los Angeles was in crisis. Streets were gridlocked with streetcars and private vehicles. Streetcars couldn’t meet their timetables, regularly faced one hour delays just to leave downtown 4.

TURNING POINT

I wonder if the four years from 1920 to 1924 were the most critical in Southern California’s transportation history.

In 1920, after much debate, the city council passed a strict downtown parking ban. April 10, 1920: that was the day it went into effect. The ban worked. The police chief noted a fifty percent improvement in traffic flow. Streetcars could meet their schedules for the first time in years 5.

How long did the parking ban last?

Nineteen days.

A silent film star led tens of thousands of motorists on a central city protest, deliberately clogging streets to protest the ban 6. Downtown merchants were distraught. Their customers were voting with their wallets and steering wheels, taking their business to stores outside the restricted zone 7.

Los Angeles gutted the parking ban. In the years that followed, the city chose not to fight the personal car, but to channel future growth around it. Leaders crafted and voters approved the Major Traffic Street Plan in 1924, which widened streets, improved conditions for drivers 8. Ten years later, the city even extended Wilshire Boulevard through historic Westlake Park — desecrated the park, some would say — purely to accommodate autos.

The die was cast. The heyday of freeway construction wouldn’t come for several decades 9 , but was part of the same pattern.

And the streetcars?

New streetcar lines already had become unattractive investments, not just in Los Angeles, but nationwide. Streetcar services were regulated, unionized. World War I had helped inflate costs, and transit workers won wage increases, but politicians feared voter wrath if they approved fare hikes. Unregulated jitneys — private motor cars — could raid transit routes, skimming the cream from fare revenue 10. Streetcar franchises often survived only because they could rely on the deep pockets of their electric utility company owners 11.

But they did survive … or did until the events I am about to describe: the conspiracy.

CONSPIRACY

No other subject is so controversial in the history of United States public transit. Not remotely. The curious will find books, articles, web sites, six archived comment and complaint pages related to the wikipedia article, even a documentary. Although there is plenty of bias from the left on this issue, I also detect, but cannot prove, an ongoing effort to massage public opinion in some related writing online. (“Nothing to see here, let’s move on.”) It seems particularly outrageous to refer to the conspiracy as a myth or a legend, given that the conspirators were accused, brought to trial and found guilty on one of two counts.

The story begins with General Motors’ interest in the bus business. New car sales had doubled from 1919 to 1923, but then had slowed 12. To G.M. chairman Alfred Sloan, the transit market looked promising 13.

In 1932, G.M. created a company called United Cities Motor Transit to finance the conversion of streetcar lines to buses. United Cities replaced streetcars with buses for bankrupt, Depression-era transit agencies in Michigan and Ohio 14.

The American Transit Association cried foul. They wanted United Cities to fix the existing electric streetcars, not rip up the whole works and swap in buses. Eventually, ATA voted to censure United Cities 15. That was bad public relations for image-conscious G.M. 16. G.M. shut down United Cities … but, it didn’t give up on the transit market. Instead, it now operated behind the scenes 17.

Staff in the G.M. bus division already had a relationship with a bus company owner, Roy Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald was small fry by G.M. standards, had only a sixth grade education 18, but G.M. could use him as a front man. They helped him with financing, with accounting, with legal issues, helped him research streetcar lines that he could profitably take over, gut, replace with buses 19. They helped him form a public company, National City Lines, to expand operations 20. Other corporations joined in. Firestone, Standard Oil, Philips Petroleum, even Mack Trucks, a G.M. competitor. All hidden from public eye 21.

And then, an unexpected windfall:

In 1935, Congress passed the Wheeler-Rayburn act to break up the nation’s powerful electricity conglomerates. Utilities now were legally required to sell off their ailing streetcar franchises for fire sale prices 22. And National City Lines moved in, replaced streetcars with buses in city after city, Los Angeles included. United States public transit would never be the same.

The FBI got wind of the conspiracy in 1946 and brought G.M. and the other defendants to trial 23. The jury ruled ‘not guilty’ on one charge, ‘guilty’ on another. And the fine? A whopping $5,000 apiece for the corporate defendants. Roy Fitzgerald was personally fined, too: $1. One dollar 24.

How should we regard the perpetrators of the G.M. conspiracy today?

I don’t know. I wasn’t alive in the 1940s. I’ve lived long enough to see public opinion shift dramatically on some issues. Streetcars in the World War II era might have been seen as old-fashioned, old-tech, the equivalent of video cassettes and answering machines. For all I know, the conspirators might have wondered how anyone could blame them for providing public transit service in new buses to cities with corrupt, bankrupt, mismanaged streetcar franchises.

But I feel very differently about the consequences of replacing streetcars, and here I rely less on what I have read than on my years of observing U.S. public transit controversies from the sidelines. Over the long-term, from the 1940s to today, I see the consequences as catastrophic.

Before National City Lines, the dozens of affected U.S. cities had working rail infrastructure. Service might have been lacking, but riders knew they had trolleys, knew where the stops were, knew that taking electric rail transit from point A to point B in their home towns wasn’t a pipe dream.

But how did they feel twenty or thirty years after NCL ripped out the tracks? Good luck finding anyone in Los Angeles now with personal memories of the Red Cars. The streetcars might as well have never existed. How can a transit agency improve service on a rail transit grid that no one remembers, that no living resident has ever used, that exists only in a history book?

I haven’t hunted for research to back me up, but believe that American attitudes toward the personal car changed gradually after the 1950s, and perhaps especially with the freeway revolts of the 1960s and 1970s. (‘This isn’t working. Our kids have asthma. The freeways are destroying neighborhoods.’) But by that time, the transit infrastructure in these NCL-hit cities was auto based. Transit agencies couldn’t offer an alternative that residents had used, could see as real.

And now, focusing again only on Los Angeles:

MISSED OPPORTUNITY

In the 1970s, Los Angeles’ planning director Calvin Hamilton introduced an innovative new General Plan for sprawling L.A. The Plan’s “Centers concept” would have channeled future city development around thirty-five high-density centers linked by mass transit.

The plan was never implemented, even after the California legislature passed a law requiring that Los Angeles rezone according to Hamilton’s plan. Hamilton was ousted. In Reluctant Metropolis, William Fulton writes that the region’s Democratic developer power structure hated Centers 25, that it threatened their modus operandi for profitable land development. I know only how painful it is for this former Angeleno to look at the 1970 Centers map blueprint online, even a half-century later. The planners obviously knew their city well and had crafted a realistic, sober approach for shifting regional focus to public transit.

I wonder if Centers was the region’s last serious chance to fix Los Angeles mobility issues. Earlier proposals for a monorail had never come as close to fruition, despite the manufacturer’s offer in 1963 to finance construction.

PROSPECTS FOR THE FUTURE

Some of the transit defenders I knew in Los Angeles made much larger personal sacrifices for transit than anyone I know in Spain. They deserve to ride the best. Unfortunately, I see no realistic prospect for meaningful change, and don’t see much point in making suggestions that wouldn’t or couldn’t be implemented. For several reasons:

(♦) Los Angeles is a fully mature city that developed around the personal car. Angelenos’ favorite gyms, pharmacies, theatres, day care centers, parks, tennis courts, churches, restaurants already exist on a driver’s grid. Locals are accustomed to thinking of location in terms of freeway exits and traffic thoroughfares.

(♦) Stigmatized transit. Californians lack personal experience with Western Europe-caliber transit, have ample reason to see new transit projects as scams. They are strongly and repeatedly encouraged to smell scams by …

(♦) … exorbitant U.S. transit construction costs. A 2008 paper for the European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research reports costs-per-kilometer roughly five times higher for Los Angeles’ North Hollywood metro extension than for the Madrid Metro extension in the late nineties. Five times! And I now wonder if California will ever connect Los Angeles to San Francisco by high speed rail, despite the more than five billion dollars already spent on the project. (In contrast, Spain has offered equivalent service between Madrid and Barcelona since 2008.) If you lived in California, wouldn’t you think ‘scam,’ too?

And finally, a point that always has to be remembered when considering the region’s future: the threat of earthquakes.

I was in Northern California for the Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989 and in Southern California for the Northridge quake in 1994. I remember the headlines, the nonstop local news coverage, how frightened, upset and insecure people felt. I also remember knowing in my heart that both of these earthquakes were as nothing, mere hiccups, next to the long-awaited, long-feared ‘Big One:’ the cataclysmic earthquake that experts have long predicted for the San Andreas fault.

The Big One is overdue. ‘Ten months pregnant,’ one expert has said. The San Andreas is ‘locked and loaded.’

Our ancestors built cities without modern scientific knowledge of how earthquakes, hurricanes and other natural disasters threaten some regions. Now that we have that knowledge — or more knowledge, anyway — we know that some global cities shouldn’t have developed where they are. Tokyo. Jakarta. New Orleans. And, unfortunately, Los Angeles.

9/17/2022: Style edit, second paragraph. That’s what I get for posting at night.

- Scott L. Bottles, Los Angeles and the Automobile, (University of California Press, 1987), Pgs. 38-40

- Bottles, pg. 55

- Bottles, pg. 93

- Jeremiah B.C. Axelrod, Inventing Autopia, (University of California Press, 2009), pg. 16

- Bottles, pg. 82

- Axelrod, pg. 17

- Bottles, pg. 83

- Bottles, pgs. 111-113

- William Fulton, The Reluctant Metropolis, (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), pg. 134

- Stephen B. Goddard, Getting There, (University of Chicago Press, 1994), pgs. 121-122

- Goddard, pg. 128

- Goddard, pg. 125

- Edwin Black, Internal Combustion, (St. Martin’s Press, 2006), pg. 208

- Black, pgs. 214-215

- Black, pg. 215

- Goddard, pg. 127

- Black, pg. 215

- Goddard, pg. 123

- Goddard, pgs. 127-128

- Black, pg. 222

- Jonathan Kwitny, The Great Transportation Conspiracy, (Harper’s Magazine, February, 1981), pgs. 18-20

- Goddard, pg. 129

- Black, pgs. 242-243

- Black, pg. 245

- Fulton, 48-51