I’ve never worked at a place like the HM&F factory brooded about in Brothers of the Milky Way, but did once have a job that inspired my description of Hank’s miseries there.

I was just out of college, a few years younger than the artsy fellow shown with the preposterous old microbus elsewhere on this blog. I had planned and budgeted badly, and found myself on my uppers, with rent due and an empty pantry. My friend Tom said he might be able to talk me into a stint at his cabinetry shop. His boss said yes; I started the next day.

HM&F is described as pretty villainous, but I feel only sympathy for the fellow who owned this cabinetry shop, even if he might have come close to costing me a few fingers. I’ll call him Mike. Mike was no older than thirty, an honest, unassuming, high school educated carpenter who had figured out that he could make money selling cabinetry to Bay Area retailers, and eventually required assistants to keep up with orders. Abracadabra: a business was born. Mike had some things to learn about workplace safety, but the labor was honest, and he created employment as he earned his keep.

Alas, like Hank — in this case, precisely like Hank — I wasn’t no William Woodworker. My friend Tom might have enjoyed his days at the shop, but Tom was a real carpenter. I wasn’t. I couldn’t be assigned to pleasurable tasks requiring skills I didn’t have. All that was left for me was the sanding room.

I will quote Hank: man, was that bad. Man.

It didn’t seem that it would be that way when I walked in. I remember a broad table, a hefty shop light overhead, and the face mask I wore, so I would not baste my lungs with lumber particles. The work was simplicity itself. I wrestled pieces of varying dimensions on the table, bore down on them with a hand-held electric sander, sanded the heck out of them. I probably paused occasionally to load the device with sanding sheets of different grit, or roughness. Easy stuff. Lassie could have managed it with her forepaws. Maybe even Mr. Ed.

How monotonous and exhausting it was! I had done other repetitive, tedious tasks, but always had been able to set aside a vital fraction of my cerebral lobes for daydreams, and thus could while away the hours without suffering. I couldn’t in that sanding room. I don’t remember why not; Carter will still president then, I think; it was too long ago. I remember only how interminable the hours became, how desolately I pleaded with seconds and minutes to scurry past to morning break!!! lunch!!! relief!!!, and how the seconds and minutes cruelly refused, instead dug in their chronological heels and waddled like drunken old tortoises around the clock face.

Never before or since has time passed so lethargically. I would pant through my face mask as I hustled around a block of wood, and order myself to stop sneaking glances at the clock. Perhaps the minute and second hands would unstick and resume their usual canter if I just stopped staring so hard.

That didn’t work. I grit figurative teeth, tried harder, made a humorless game of it. Don’t look at the clock. Don’t look!

One morning I kept my eyes off the dial on the wall for what had to be an hour, simply had to be, as I wielded the sander and puffed through the mask and hoisted one wood piece after another on the table.

Finally I permitted myself a glance. At least an hour had gone by; I knew that. At least. I had to look now, didn’t I? Wasn’t it almost time for lunch?

More than thirty-five years later, I can still taste the bewilderment and despair I felt in that moment when I raised my eyes to the clock.

It hadn’t been an hour.

I had used up only fifteen minutes.

* * *

After the first day, I headed straight home, staggered to bed and slept for at least twelve hours. Maybe fourteen. I soon became a little better acclimated to the work, but was always exhausted when I left, and in this exhaustion felt defeated, beaten. I wanted to write every day back then, in my literary twenties, but quickly gave up any fantasy of that while I worked in the sanding room. If I had been more practically ambitious, I would have required someone to hold a twelve gauge on me to get me to wash up and drag myself to an evening college course. I looked with new sympathy at the laborers I saw after work in neighborhood supermarkets. I finally understood why they looked so gray and grimy and half-asleep. That was how I looked now, too.

* * *

One morning after about two weeks of this, Mike took me aside when I arrived for work. He had a new job for me.

Mike wanted me to spend the day with the table saw.

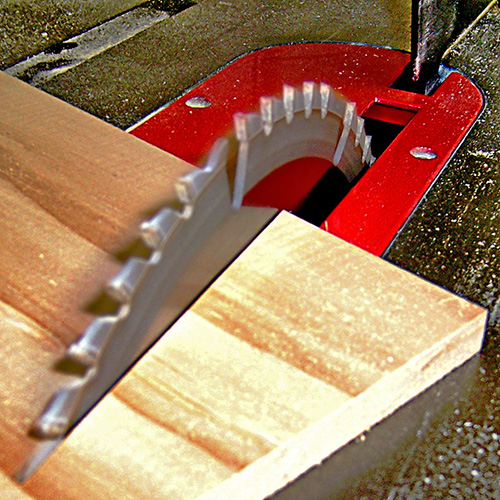

I have scoured Flickr for a Creative Commons-licensed photo of a table saw, as I am too lazy to dust off my camera to take my own. (Thank you, Patrick Fitzgerald, whoever you are; an excellent shot.) The table saw shown is much newer than the rickety old monster that stood imperiously by itself near one of the shop doors. The blade, however, was similar.

Admire that blade for a moment, gentle reader. A big mother, isn’t it? Sharp, too.

Imagine that blade at speed.

What do you think that blade would do to your finger, if your finger were to get in its way? Would the blade politely stop in its mad spinning, do you think, so your finger wouldn’t get a nasty ouchie-wouchie? Or would it lop off your finger like a match stick, and render you newly finger-less?

If you think it would politely stop, please take a moment to scan one or both of the articles below.

http://www.popularmechanics.com/home/reviews/power-tools/4286772

“We’ve got a pile of wood that needs to get cut,” Mike said. “This should keep you busy all day.”

Mike flicked the ‘on’ switch. The monster sprang to life. WHIRRRRR. HUMMMMMMMM.

Mike fetched a piece of wood to demonstrate the saw’s operation.

I stared at the blade.

I am writing this post in my late fifties. On the keyboard beneath the screen are all ten of the digits I sprang from the womb with. My socks might smell a bit, but there are ten toes in them. I am grateful to still have both legs, both arms, both ears. I believe that all of us flower into maturity with an inheritance of survival instincts passed on from late, great ancestors. My portion of survival instincts had generally served me well.

They were about to serve me well again. As one, in a chorus, the ancient Russkies and Krauts and Limeys and Scots who had contributed DNA to my chromosomal bouillabaisse arose from their fourth dimensional graves, and bade me in unison:

PAY ATTENTION TO THAT SAW, TIM. TIME TO WAKE UP. BUDDY. TIME TO WAKE UP FAST.

“Isn’t there supposed to be a guard for the blade?” I asked.

I tried to sound only idly curious. Men much my junior also try to sound idly curious when asking Sports Illustrated swimsuit models if they are free for coffee, or if they have boyfriends. They’re not idly curious. Neither was I.

“Well, no. Sorry.” Mike looked self-conscious. “If you’re worried about your fingers, you can push it through with a push stick.”

Mike demonstrated, using a short piece of wood scrap to nimbly guide a 2 x 4 through the viciously spinning blade. (Yes, for you carpenters: a dinky wood scrap. Not a proper push stick or push pad.) He was a thoroughly experienced wood worker, had probably spent nearly every work day in the shop for the past ten years.

HE KNOWS WHAT HE’S DOING, TIM, hollered my Russian and Teutonic and British ancestors. YOU DON’T. PAY ATTENTION TO THAT SAW, TIM.

“You’ve got to be careful with her, though,” Mike said. “If you don’t feed the wood through right, she’ll kick it back at you.”

She’ll kick it back at you. I quickly sought an amplification of this advisory, with no more pretense of idle interest. Mike explained that the table saw was old and in less than ideal repair. If unhappy with how it received a piece of wood, it might “kick” that wood back at the woodworker. Hard. Fast. Imagine a newly-wed ingenue with Gloria Allred on the speed dial before the honeymoon starts.

“Does it do that often?”

Mike looked self-conscious again. I thought he avoided my eyes.

“Well … it happens. You’ve just got to be ready to duck.” Mike shrugged. “Just stay out of the way of it.”

TELL THIS GUY WHERE TO STICK HIS TABLE SAW, roared my ancestors, and waved their cossack hats and teutonic horned helmets. HIT THE ROAD, TIM. MAKE WITH THE FEET.

Diplomatically, I expressed misgivings. Mike looked apologetic, and said he didn’t have any other work for me. My William Woodworking stint drew to an undignified close.