The block universe theory holds that our human perception of time misleads us, that past, present and future are equally real. Or that’s how I understand it, at least, as a lay person. I sit at my Madrid computer, blink at the display as I type these words; a doctor tugs my wailing, bloody newborn self from my mother’s body, cuts my umbilical cord; I die, at a time and in circumstances unknown to the blinking Madrid typist but in an event as certain, fixed and unalterable as was my birth and is my present.

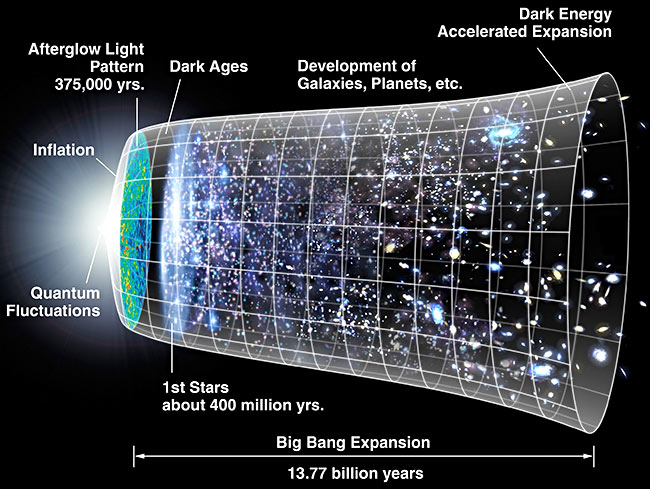

“The past, present and future,” said Einstein, “are only illusions, even if stubborn ones.” A comic compared a human life in our four and a half billion year old earth to a raisin baked into a spectacularly large cake. One can hope that one’s raisin is sweet and large, but it is what it is. Your figurative raisin was inevitable and fully formed when neanderthals crafted seashell jewelry on the Spanish coast 115,000 years ago. No; earlier: when the universe was born.

Perhaps I should apologize for this post. It has nothing to do with expat-in-Spain issues, or transit, or travel, or anything else I usually write about here.

I’m sorry. I’m interested in time. I wrote about it here once before.

I first encountered the term ‘block universe’ while trying to understand Einstein’s relativity theories. Or, more accurately, while trying yet again to fathom them, for the umpteenth time in more than forty years. My interest often has felt masochistic. I’m not a physicist or a mathematician, had acknowledged from the start that a lay person could only make so much headway with such exotic material. But what I did understand intrigued me, and so I tried again and again, with a new book, article, video or a review of what I’d read or seen before, stubbornly, doggedly, like a repeatedly-felled boxer who won’t stay on the canvas.

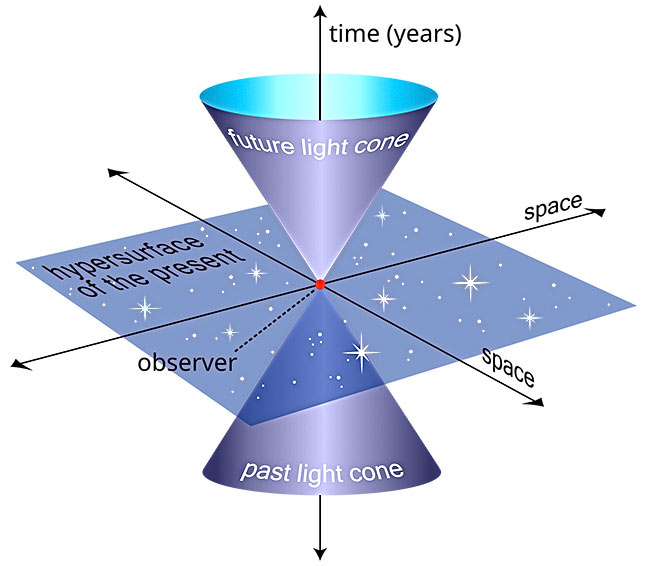

My efforts hadn’t all been in vain. Some elements had sunk in. That the speed of light is constant, fixed, at least in a vacuum: almost 300,000 kilometers per second, y ya está. That it is space and time, in contrast, that are elastic, not in the realm we inhabit, but on the scale of planets, stars; when things get very, very heavy or go very, very fast. That the three dimensions of space and single dimension of time can be regarded as a single mathematical model, and seen as one: as spacetime.

I thus wasn’t caught completely off guard by the notion of a block universe. If time is a dimension — this elastic time, that could be said to stop at the speed of light, that could itself end — why should our inability to see more than one forward-ticking point on the timeline mean that all the other points aren’t equally valid, equally real? I can’t see infrared or ultraviolet, but they are made no less factual by my limitations. A three-dimensional sphere passing through a two-dimensional plane might be recognizable on that plane only as a series of variably-sized circles. A two dimensional inhabitant of that plane might bitterly deny that a sphere can exist.

So I had something new to think about, a tasty cognitive chewing candy reward for all my hours of suffering with the relativity theories. I contemplate past moments of my life — stepping into the batter’s box in Little League; scattering my mother’s ashes on the California coast; riding the taxi into Madrid from the airport in 2016, with my suitcases in the back — and acknowledge that these moments are still vital and real and happening now, but in a ‘now’ that is inaccessible to me, on another point on the timeline.

Further, so also are occurring moments that the blinking Madrid typist as yet knows nothing about: my certain death, perhaps a planned, civilized leave taking at a Swiss clinic if I become unmanageably infirm, or perhaps a death that is sudden, messier, with ambulances, blood. A frail, wizened Tim may shift withered limbs in a Sarco pod, may press the button to release the life-concluding nitrogen. Maybe. I don’t know. But the future event is certain, immutable, could be regarded as ‘written,’ as some theists like to think. I can’t change it. I move toward it inexorably.

I could feel resentful, if I wish, used. What free will do I have? I had imagined the Big Bang as a throwing-open-of-gates to a spontaneous, too-colossal-for-words improvisation, with free will and no known outcome. What if it would be better compared to the first frames of a finished, in the can, billions-of-years long movie? One could say that I don’t even qualify as a life actor, in this scenario; I’m a robot, a connector of four dimensional dots. What choice do I have about anything?

Or maybe both of these comparisons are valid.

I believe I do have free will, or perhaps a free will with constraints that aren’t relevant to me.

Something like this:

Scenario 1: I vacation on the shore with friends, stroll a cliff towering over the ocean, and am so absorbed in our debate about a block universe that I meander too close to the edge. The ground crumbles; I grasp desperately for a hold as I topple off the edge, and manage to grasp a root jutting from the face of the precipice. From it I dangle, as my friends scream for help.

Minutes pass. The root is sturdy, but cuts into the un-calloused flesh of my finger pads. My hands, wrists, fingers throb, ache excruciatingly. In my agony I dazedly recall our interrupted talk about the block universe, and feel mocked by a cruel universe to be so reminded. What difference does such theoretical stuff make now?! I have to hold on!

And do, until help arrives. I am rescued, survive, will later joke with the doctor who treats my hands.

Scenario 2: Identical to Scenario 1, except that I try to relieve my tortured hands by changing my grip on the root. A final, fatal mistake. There will be no later repartee in a hospital. I lose my grip, topple to my death.

In Scenario 1, at that date and time and place, I do, always have and always will fall from the cliff, grab the root, and survive.

In Scenario 2, at that date and time and place, I do, always have and always will fall from the cliff, lose my grip and perish.

The theory changes nothing in a human experience of the scenarios. In both, I have what I think of as ‘free will.’ But the unknown-to-me outcomes are certain.

As were and are the final words of this post, long before I thought of writing it.

Lead image credit: MissMJ, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

About predestination …

Never believe an untestable theory.

I couldn’t resist asking Bard, and it agreed.

But it may have been predestined, too.