5,300 years ago, this doomed man ate a last meal on the mountain glaciers of today’s Northern Italy. He may have struggled to grasp food. He was right-handed, ate despite a fresh, deep gash that reached to the bone of that hand, perhaps sustained in a brawl in the valley. He might have climbed the mountain to flee enemies.

Ötzi, we call him today. He was about forty-five, trim, gap-toothed, heavily-tattooed, bore a copper ax that may have marked him as a tribal leader. On the glacier he dined last on ibex meat, einkorn wheat, bracken, fat.

He had minutes to live. An enemy shot him from behind half an hour after he ate. The arrowhead pierced an artery. Ötzi bled to death, fifteen centuries before Hammurabi issued his code of law, three thousand years before Alexander the Great claimed Persia. He died on the ice that preserved his remains for the next five millenia. He is the world’s best-preserved mummy.

Why tell you about him?

I’ve felt since summer that I’ve figured something out. It’s not anything mystical; I don’t walk around hugging strangers, still get mad at robocalls. Maybe I’ve been dense; maybe most of you figured it out long ago. But I hadn’t, and it’s important, at least to me, and if I can explain it maybe I can help someone else figure it out too.

Bear with me. Please. I don’t know how to explain it quickly. I have to tell it in pieces, try to tie them together at the end.

* * * * *

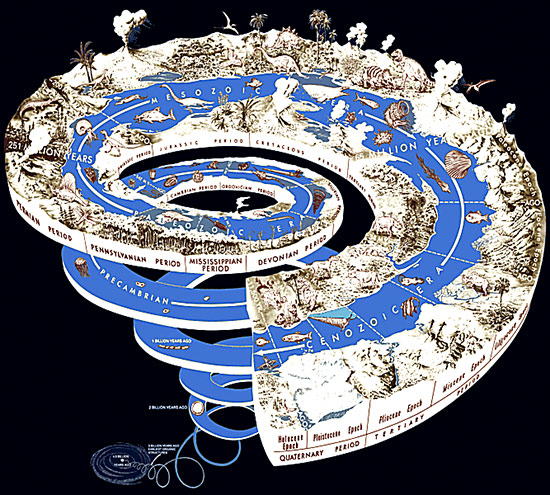

The Geologic Time Spiral, is what USGS calls the illustration below. Click here to see it full size. Feel free to stare at it for awhile. I have. Four and a half billion years in a single .png, from planetary birth to skyscraper-dwelling present.

I stumbled into the Time Spiral about ten years ago, while hunting for a visual to show students at the Los Angeles Tar Pits. “Slick,” I thought, and peered at the little pictures of fishies and dinosaurs and cave people, and tried to memorize the difference between ‘Quaternary’ and ‘Jurassic,’ so the kids would think that their field trip guide knew his stuff. Pretty soon I forgot about it. I had classes to teach, TransitPeople trips to lead and plan.

This summer I remembered the graphic and decided to study it longer. It was important, I decided; it had something to tell me, and maybe I could get the Something if I stared at the graphic long enough. I pulled the .png into a photo editor and made it into a Linux start-up screen, and sweet-talked myself to linger on the pictures and words and numbers every time I logged in, not to memorize ‘Quaternary’ or ‘Jurassic’ but to get something, a big picture. To let it sink in.

It did. Or started to.

3 BILLION YEARS AGO EARLIEST ORGANIC STRUCTURES, the poster says. See the little round empanada thingie at 2 BILLION YEARS AGO? A eukaryote, I think. Global life hadn’t gotten much farther than cells with nuclei at that point, two and a half billion years after planetary birth. A notch up from bacteria. The critters don’t start to proliferate on the time spiral until CAMBRIAN PERIOD and the dashed 542 M.Y AGO line.

Before the Cambrian, for nearly nine tenths of its four-and-a-half billion year history, the world was mostly free of visible life. Oh, you had bacteria, and the eukaryotes, and eventually weird, flat, brainless huggers-of-the-ocean-floor Charnia and Dickinsonia. But nothing like what we regard as ‘life’ today. The land was barren. No plants on earth. No animals. At the start of the Cambrian, the planet didn’t even have a breathable-by-humans atmosphere.

Think about the scale of time involved.

Where do you want to peg the starting line for human civilization? Debateable, I know, but I’ll use Uruk, ancient city of Mesopotamia, founded about 4,000 BCE. Six thousand years of recorded human civilization. A nice round number. My grade school ancient history book started with Mesopotamia.

Fire up a calculator, make some comparisons.

How many of those six thousand year, practically-all-of-recorded-human-history blocks could you fit into the four billion years of the mostly lifeless pre-Cambrian?

Fundamentalist numerophones among you, cover your eyes: 666,666. Two thirds of a million. The first time block is to the second what the weight of an average American adult is to seven and a half Eiffel Towers, what a single meter is to a 400+ mile trek from Baltimore to Boston. That practically-all-of-recorded-human-history block amounts to less than 2/10,000th of one percent of the eons when the earth did its planetary thing without oxygen, plants, animals: a mostly blank slate, a fresh-gelatin-in-a-petri-dish kind of world.

Which isn’t news, of course; which the profs have tried to explain, many times. The football field analogy, the tip-of-a-human-hand analogy, the all-of-life-in-an-hour analogy. It’s too huge, we can’t bend our brains around the comparison.

In the millions of years after the Cambrian, awareness evolved.

“One and a half walnuts” describes the brain size of an ampelosaurus, an eight thousand kilo dinosaur that roamed Spain seventy million years ago. A plant-eating machine, as big as a tow truck, about as smart. I can’t credit it with anything I would recognize as feeling or thought; I presume that it foraged, mated, lay eggs, perished without awareness of its inhabited world, without consciousness, emotion, memory.

But would I dismiss a mammal’s life experience so off-handedly? The internet offers innumerable videos that suggest animal emotion: a dog lobbying for seconds, a cow distraught for a newborn calf, the brutal mating saga of lions. Experts debate: are animals conscious? Will a nightmare of her cubs’ past slaughter ever disturb an aging lioness’ sleep?

55 mya: the first primates. 8 mya: gorillas. 4 mya: australopithecines walked upright on the African savannah. Slowly, effortfully, painfully, we evolved, developed the intellect and technology to insulate our vulnerable bodies from merciless nature, developed the mind to become human.

2 mya homo habilis split rocks, wielded stone tools. 1 mya homo erectus controlled fire, built wooden huts a half million years later. 400,000 kya: homo heidelbergensis hunted with spears. Long-distance trade at 140,000 kya (we homo sapiens were around by then); 30,000 kya — twenty-four thousand years before Mesopotamia — the Chauvet cave paintings.

No one knows how many of our ancestors peopled prehistoric earth. Ten to thirty thousand may have lived when homo sapiens emerged; millions, by Ötzi’s time. I try to picture daily life in the prehistoric millenia, recoil in horror at what I imagine. To abide in the shadow of hunger and want from infancy to infirmity, driven to stalk game across rocky slopes on aching, bloody foot soles, with only animal skins to protect vulnerable bare skin in freezing winter. Always with the reproductive urge intact, so that our benumbed progenitors would bring forth suffering new life into the cruel world. Injuries today easily mended — a fracture, a cracked tooth — might doom their victims to years of constant pain.

From their hundreds of thousands of years of suffering emerged the astoundingly complex spectrum of life we know today. The debt we owe to our cold, starving, injured, unremembered prehistoric ancestors is immeasurable if we value our (admittedly, often still miserable) lives at all. Because it was not just the paraphernalia of modern life that emerged — smartphones, duplexes, heaters, broadband, traffic, skyscrapers — but our modern human capacity to think and feel on the figurative terrestrial stages made by these human-constructed paraphernalia, to take their existence for granted, to accept set-dressed stage as life, reality, the world.

Consider the fictional life slices below: random vignettes, the last excepted, pulled out of a figurative hat. Consider their dependence on paraphernalia and social customs, how the paraphernalia and customs comprise environment, mark boundaries.

Her blind date was waiting at the bar, as promised, sporting belly and wrinkles at least thirty pounds and fifteen years north of his online dating profile. A classic kittenfisher.

Oh, yuck. Could she bail? No; he’d already spotted her.

Lisa forced a weak smile, aware of his greedy eyes on her torso as she approached the bar from the pub door, already mulling an exit strategy. She should have Skyped the SOB first. Internet dating could be so depressing. She’d never get married.

(21st century paraphernalia: bar, internet, dating app, mating rituals, buildings, photos.)

The cubicle barrier shook as Jim staggered into it, twenty minutes late, stinking of weed. Paul muted his support call, glared at his coworker.

“Would you watch out?!”

Jim only blinked at him fuzzily, clothes disheveled, brown droplets of a morning frappe glistening in his beard. Paul turned back to his support call, stifling pity, disgust. Jim had to be the worst CSR on the planet. How desperate could management get? He ought to short the company stock.

(21st century paraphernalia: cubicles, customer support departments, buildings, telephone)

Ötzi huddled under the mountain outcrop and tried again to make fire, trapping the fire stone under the bloody right hand crippled by the boy’s dagger, chopping away with the flint striker clutched in his left. But it was hopeless. He was right handed, couldn’t strike properly with his left. He’d never get a good spark, not here, and even if he did he wouldn’t be able to move his hands nimbly enough to nurse fire in the tinder at this altitude.

Grimly, he returned the fire tools to the pouch. He stepped away from the outcrop and gazed to the wooded valley far below, watching for movement under the valley tree line and on the jagged, bare rock between the valley and his summit.

The brothers would be coming for him. They wouldn’t forgive him for killing the boy. With arrows he could defend himself — could ambush the brothers, perhaps kill all three, if he caught them in the open on the bare slope and could control the bow string with his maimed hand — but he had only two arrows in his quiver and without fire couldn’t heat birch tar to finish more, to glue the fletchings to the arrow or the arrowheads to the shaft. He would have to retreat.

(Ancient Chalcolithic age paraphernalia: fire starting, arrow making)

A half-dozen more century-spanning examples, in short form, plucked from the millions afforded by the human experience:

– a sunny summer skate under the beachfront palms, ear buds in, popping fingers to the latest on Spotify

– nervous, set-jawed, a rookie pilot takes the helm of a steamboat in Mark Twain-era Mississippi

– muttering a quiet prayer while tearing open the registered letter with the test results

– wide-eyed children watch soldiers nail a bloodied activist to a crucifix in first-century Judea

– a boy’s crush on a nun in the Middle Ages

– killing time at the airport departure gate with smartphone videodocs on hoarders and fat shaming

“Is life an illusion?” a metaphysician may ask, amidst talk of quarks, quantum mechanics, string theory. I can contribute no opinion, but note how indisputably — obviously, transparently — invention and custom mold our life experience, as the set dresser’s chairs, table and ice box transform a bare theatre stage to Willy Loman’s kitchen. A child unravels an elaborately patterned sweater, stares wonderingly at a handful of yarn, goggles at the understanding that the sweater was never anything more.

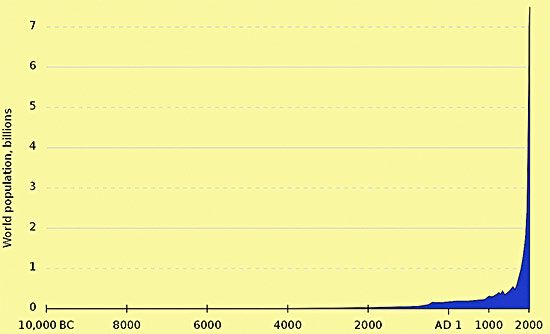

And all of it so shockingly new, in the greater scheme of things! The graph above shows our world’s homo sapiens population for the twelve thousand years of our current Holocene Epoch. Physicist Stephen Hawking described our species as a chemical scum; I marvel at how decisively and rapidly the scum has expanded, spurred by brain volume, opposable thumbs, bipedalism, speech capacity, how our species now dominates and threatens its host.

Whimsically, without evidence, I wonder if we might be the point of it all.

Or part of the point. Our mind: individually, collectively.

* * * * *

He had food left. His hand had kept him up most of the night; he needed strength. Ötzi ate, staring steadily at the distant valley as he chewed goat meat, watching for the approach of his enemies. When he finished he turned to the trail that traversed the mountain pass and began to trudge away from the valley that had been his kingdom, that he had ruled for a hundred moons. He would meet traders eventually. If he had to, he could barter the ax. A final indignity.

The sun emerged from cloud cover, shone bright on the bare, jagged gray rocks and the ice sheets flanking the mountain trail. Ötzi hiked on. Moodily he reflected on a dream message The One had offered the night before, a fleeting clarity in his fitful sleep.

The brothers might drive him from the valley he had ruled, The One had said; Ötzi might be forced to trade his tools for food in foreign lands, even the ax, symbol of his rule. But his life would be remembered: not for a dozen moons, not for a hundred, but for tens of thousands, for as long as humankind dwelled on soil; would be pondered by tribes beyond all imagining of people today. The brothers may have stripped his kingdom, but The One would bestow immortality. The world would never forget that Ötzi had lived.